At the Musée de l’Orangerie, Claude Monet’s vision reaches its most immersive and meditative form. Conceived by the artist himself as a “refuge of peaceful contemplation,” the Nymphéas (Water Lilies) cycle unfolds across two oval rooms bathed in natural light, inviting visitors to step inside Monet’s world rather than simply observe it.

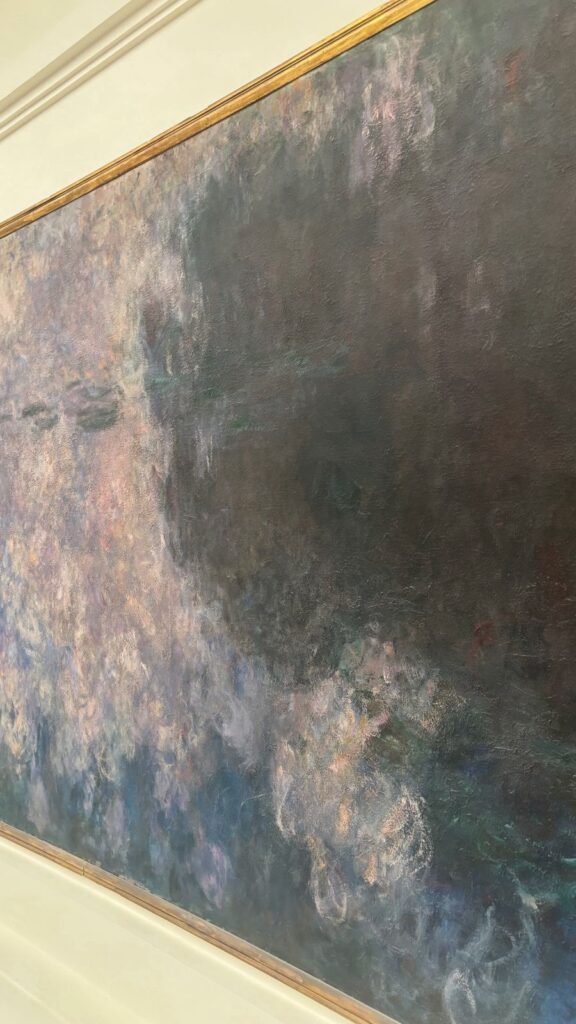

Painted in the final decades of his life, when his eyesight was failing, these monumental panels abandon traditional perspective. Horizon lines dissolve, reflections blur into water and sky, and time seems suspended. What remains is sensation: light shifting, colors breathing, nature in constant transformation. Monet was no longer painting a landscape, but an experience.

Installed here in 1927, shortly after the artist’s death, the Orangerie became inseparable from the Nymphéas themselves. The space was designed to echo Monet’s philosophy, art as solace, as rhythm, as a quiet counterpoint to a world recovering from war.

Today, standing within these curved walls, one does not simply look at Monet. One lingers, drifts, and listens. The Orangerie offers not a retrospective, but a living dialogue between painting, space, and silence a final masterpiece by Claude Monet, completed not on canvas alone, but in architecture and light.